By Capt Elizabeth Garza-Guidara

Introduction

El Salvador’s status as a paper Leviathan democracy can be attributed to the prevalence of authoritarian elements in its political, economic, and law enforcement institutions. These elements have led to state-sponsored violence, an economy of crime, and the emergence of non-state actors that can challenge the state and impact the electoral process. Furthermore, it is crucial to explore the emergence of MS13 as a response to the Salvadoran state’s systemic disenfranchisement of abandoned youth in the country’s post-civil war era. This is crucial to understanding Mara Salvatrucha’s (MS13) ability to wield political power and influence in El Salvador.

The purpose of this article is to explore the extent to which the Salvadoran government’s employment of punitive populism has increased MS13’s political power in El Salvador from the early 2000s until the present. This research is critical in not only investigating MS13’s evolution as a political actor, but in demonstrating to what extent the Salvadoran government continues to collaborate with the gang as well. Although El Salvador’s current presidential administration under Nayib Bukele preaches the government’s commitment to being tough on crime, a number of investigations against the Bukele administration suggest otherwise.

MS13 is an expression of endemic poverty and marginalization. The gang cannot be degraded unless socioeconomic inequalities are fully confronted at a structural level. Increased government brutality against gangs has proved to ironically strengthen MS13’s strategic organization and commitment to interacting with the Salvadoran government as a political entity. Additionally, the anecdotal evidence described in this article signals the corrupt links between government and MS13. By investigating MS13 as the offspring of the Salvadoran government’s persistent employment of punitive populism, this article seeks to answer the following question: How has MS13 capitalized on weak Salvadoran state governance to increase its political power in El Salvador?

Punitive Populism as an Enabler of MS13’s Political Power

In order to understand the nature of MS13’s political power in El Salvador, it is necessary to explore two phenomena: 1) the gang’s evolution within the framework of the Salvadoran government’s employment of punitive populism and neoliberal reforms and 2) how the gang’s political power mechanisms are derived from its abilities to control votes, to serve as an electoral voting bloc, and to control local and national homicide rates. In regard to the first phenomenon, punitive populism embodies the principle that public support for more harsh criminal justice policies serves as a catalyzer of policy making and political elections.[1]

Punitive populism emerged as a result of the survival and persistence of authoritarian institutions in the post-civil war environment. According to Jose Miguel Cruz, state institutions in El Salvador sustained criminal violence by collaborating with violent actors from the pre-civil war military regime and maneuvering around policies aimed at achieving transparency.[2]

Punitive populism was also a tool used by the elites to politicize crime and stay in power. Repressive law enforcement policies (Mano Dura) were employed by elite members from the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party.[3] ARENA politicians used El Salvador’s marginalized population to stay in power by using criminal deportees as scapegoats for the dysfunctional state of the government and the subsequent justification of authoritarian law enforcement measures.[4]

According to Garni et. al., the ARENA party’s implementation of Mano Dura is intertwined with neoliberalism, which embraces macroeconomic reforms via free market capitalism and privatization.[5] While Salvadoran elites championed neoliberalism as a means of ensuring their position within society, the remainder of the population was abandoned. Wade builds upon this observation by emphasizing how the implementation of the neoliberal economic model by four successive ARENA administrations not only intensified existing socioeconomic inequalities, but also created new obstacles to sustainable peace.[6]

The ARENA party’s implementation of “Mano Dura” in tandem with neoliberal policies gave birth to MS13 and its evolution into a political actor. Farah and Babineau theorize that MS13’s political power is derived from the Salvadoran state’s weak political will and the gang’s ability to negotiate with the government for entitlements.[7] MS13’s successful bargaining with the Salvadoran government is likely rooted in multiple ties between local gang members, local government officials, politicians, and grassroots leaders.[8]

MS13’s political power is also derived from its ability to serve as an electoral voting bloc and to control political participation in territories throughout El Salvador via the following tactics: discouraging residents from interacting with government officials; residents’ fear of neighborhood violence (and the subsequent lack of an incentive to leave home and vote); and the employment of violence to deter resident interaction with state actors.[9] While Abby Cordova sheds light on how MS13’s political power is rooted in its ability to control votes in territories, Cruz reveals how this power is also derived from the gang’s ability to control the homicide rate in El Salvador. This was illustrated during the 2012 gang truce between MS13 and a rival gang, Barrio 18, that resulted in a plunging homicide rate in one year.[10] Due to the Funes administration paying MS13 up to $25 million in order to reduce El Salvador’s homicide rate, the 2012 gang truce was MS13’s major political turning point.[11]

Ultimately, the Salvadoran government’s inability to confront the gang and resolve endemic poverty and socioeconomic inequality has strengthened MS13’s political grip over El Salvador. Based off this phenomenon, it can be hypothesized that: The stronger the Salvadoran state’s employment of punitive populism, the stronger MS13’s political power will be in El Salvador. The Salvadoran state employed punitive populism via the preservation of elite power at the expense of the poor while employing a militarized law contributed to MS13’s political power, which is twofold: the gang’s ability to control the homicide rate as a political bargaining tool and its ability to influence election results. The subsequent sections of this article will explore this phenomenon’s components (and component indicators via analysis of descriptive statistics and qualitative data) and their impact on one another enforcement modus operandi (see Table).

| Component | Indicator |

| Preservation of elite power & failure to confront structural inequalities & marginalization

|

Socioeconomic equality |

| Militarized law enforcement modus operandi

|

Financial investment in the military |

| MS13’s political bargaining power | MS13’s ability to control the homicide rate |

| MS13’s ability to influence election results | MS13’s ability to control votes & serve as an electoral voting bloc |

Table: MS13 Political Power & Salvadoran Punitive Populism

Source: Author

Preservation of Elite Power at the Expense of the Poor

From 1989 to 2009, the state’s elite party, the ARENA, ruled.[12] The ARENA’s neoliberal restructuring of El Salvador eliminated the opportunity to forge a social democracy, which gave birth to punitive populism as a vehicle for deepening socioeconomic inequality.[13] Marginal increases in El Salvador’s Human Development Index (HDI) (Figure 1) also indicate that punitive populism continued to serve as a mechanism for the elite to maintain endemic poverty as the status quo for a majority of Salvadorans.[14] The persistence of socioeconomic inequality in El Salvador is primarily attributed to post-war institutions focusing more on strengthening their macroeconomic market forces instead of confronting the traumatic impact of the civil war’s economic structural shifts.[15] This was demonstrated when former Salvadoran president Cristiani tripled El Salvador’s GDP from 1986 to 1994 via neoliberal economic policies.[16] However, this surge in GDP failed to confront the nation’s socioeconomic imbalance. From 1989 to 2004, poverty levels rose from 47 percent to 51 percent.[17] By 2008, the income of the wealthiest 10 percent of the population was almost 50 times higher than that of the most destitute.[18]

As a result of this, an increasing number of adolescents were living in marginalized communities.[19] With this in mind, joining a gang not only generated income, but provided a means of coping with exclusion and marginalization.

Socioeconomic inequality in El Salvador has continued to thrive within the past decade. From 2010 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019, the HDI remained the same (see Figure 1).[20] Furthermore, the marginal increases in HDI have not increased socioeconomic equality on a large scale.

Figure 1: El Salvador’s 2003 – 2019 Human Development Index (HDI)

Source: Adapted from World Data Atlas 2018 and United Nations Development Program 2019[21]

These marginal increases in HDI also support two assessments: 1) a decrease in the homicide rate is not a result of increasing socioeconomic equality and 2) enduring socioeconomic inequality has incentivized MS13 to use its ability to control the homicide rate and votes as means of strong arming the state into fulfilling basic needs that are being neglected.

These assessments are supported by interviews with experts. According to an InSight Crime expert, the Salvadoran government’s punitive populism can be attributed to its inability to address systemic failures in tandem with its implementation of short-term solutions that fail to confront endemic poverty.[22] This expert also revealed that the Salvadoran government’s apathy towards marginalized communities can be attributed to the government’s view that investing in these communities would fund gangs.[23] This aligns with another InSight Crime expert’s assessment that the Salvadoran state continues to abandon those in poverty.[24] Furthermore, an independent researcher also highlighted the Salvadoran state’s endorsement of systematic political and social exclusion of the poor in order to preserve the welfare of the elite.[25]

Militarized Law Enforcement Modus Operandi

Punitive populism not only perpetuates socioeconomic inequality, but also champions state-sanctioned violence against the marginalized in order to preserve elite power and deflect attention away from the government’s incessant shortcomings.[26]

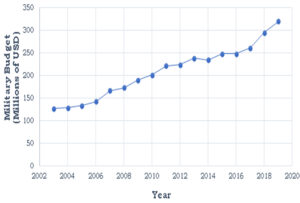

Figure 2: El Salvador’s 2003 – 2019 Military Budget

Source: Adapted from World Data Atlas 2019[27]

The ARENA’s employment of Mano Dura in 2003 and its significant investment in the military (which can be used in a law enforcement capacity) fulfilled this objective.[28] Mano Dura policies championed the definition of discretionary crimes as restricted due process rights, and involved the military in policing.[29] These discretionary crime laws enable police to arrest suspected criminals based on subjective information.[30] According to an independent researcher, the National Civil Police (PNC) continued to criminalize the poor by treating members of poor neighborhoods like gang members.[31]

A byproduct of Mano Dura was not only a militarized approach towards law enforcement, but the Salvadoran government’s increasing military budget (which includes the budget for law enforcement and paramilitary entities) from 2003 to 2019 (Figure 2). However, from 2011 to 2012, the homicide rate plummeted by nearly 50 percent while the military budget only increased by $3 million.[32] The marginal increase in financial investment in the military was unlikely to cause this drop in homicides. Mano Dura was also used by the ARENA party to gain public support for the 2004 presidential elections by depicting youth gangs as the common adversary of good citizens.[33] This strategic implementation of Mano Dura left a permanent imprint on Salvadoran society: violence was embraced as an instrument for “good” citizens to safeguard themselves against vagrants.[34] Punitive populism also restricted alternatives to the use of force. Hence, programs geared towards increasing socioeconomic equality (such as Mano Amiga and Mano Extendida) have generally been underfunded and carried out with little success.[35] Furthermore, underfunded socioeconomic programs in conjunction with a lack of a significant increase in El Salvador’s HDI from 2003 to 2019 demonstrate the prevalence of socioeconomic inequality in El Salvador (Figure 1).

Mano Dura’s failure to reform its security apparatus also led to a politicization of the PNC. Because government elites permitted military members and personnel from previous security institutions into the new police force, these individuals continued to implement authoritarian practices.[36] Additionally, the elite’s attempt to maintain authoritarian policing frameworks was aimed at ensuring the dominance of conservatism in the PNC.[37] This is supported by an InSight Crime expert’s declaration that the PNC is not only politicized, but also consists of the same thirty members who joined the PNC when it was formed (immediately after the civil war in 1992).[38] Furthermore, the presence of these police officers in the PNC illustrates the persistence of the Salvadoran government’s punitive populism.

Mano Dura’s failure to reform its security apparatus also led to a politicization of the PNC. Because government elites permitted military members and personnel from previous security institutions into the new police force, these individuals continued to implement authoritarian practices.[36] Additionally, the elite’s attempt to maintain authoritarian policing frameworks was aimed at ensuring the dominance of conservatism in the PNC.[37] This is supported by an InSight Crime expert’s declaration that the PNC is not only politicized, but also consists of the same thirty members who joined the PNC when it was formed (immediately after the civil war in 1992).[38] Furthermore, the presence of these police officers in the PNC illustrates the persistence of the Salvadoran government’s punitive populism.

The politicization of the PNC in tandem with Mano Dura policies inadvertently strengthened MS13’s political capital. A surge in MS13 member detainments provided the gang with the opportunity to strategically develop regional and national leadership, increase communication, and expand territorial control via the increased organization and union of its cliques.[39]

Controlling the Homicide Rate as a Political Bargaining Tool

Mano Dura policies not only aided in MS13’s strategic growth, but also set the stage for the 2012 gang truce and MS13’s subsequent realization that its ability to control the homicide rate was a powerful political tool. This became clear when a Mano Dura policy (confinement of national gang leadership in a single facility) inadvertently armed MS13 with the ability to mandate curfews. These curfews paralyzed the national transportation system and compelled the government to meet the gang’s demands.[40] The government responded by attempting to regain control over prisons, which incentivized gang leaders to find ways to restore their power. Hence, controlling the homicide rate served this purpose for MS13.

In 2012, MS13 and Barrio 18 agreed to a truce that sparked the homicide rate to plunge by over 50% in one year.[41] Figure 3 supports this claim by illustrating how the homicide rate dropped by 28 per 100,000 people.[42] The decrease in homicide rates was in exchange for the government’s commitment to transferring gang leaders from a maximum-security prison to regular detention centers.[43] The truce also allegedly included the transfer of thousands of dollars from government officials to gang leaders.[44]

Figure 3: El Salvador’s 2003 – 2019 Intentional Homicides

Source: Adapted from The World Bank 2018 and the US Department of State Overseas Security Advisory Council 2020[45]

During gang truce negotiations with the Funes administration, MS13 realized that it had real political power for the first time.[46] An Insight Crime expert highlighted that this power was derived from its ability to serve as an interlocuter to formal political power during truce negotiations.[47] This is made clear in the following declaration by an MS13 leader: “The government asks us what we want, and we tell them—and then they give it to us. We have found that if they say no, we just have to dump enough bodies on the street, then they say yes.”[48]

Although the Funes administration publicly acknowledged that El Salvador actively participated in the truce in 2013, the truce collapsed in 2014.[49] This occurred when the Salvadoran Supreme Court ruled that the appointment of the public security minister (who was the government’s truce plan designer) was unconstitutional since the Constitution banned military officers from filling any position in citizen security institutions.[50] The collapse of the gang truce had severe consequences. From 2014 to 2015, the homicide rate skyrocketed to 105 per 100,000 people, which was the highest 2015 homicide rate in the world.[51]

Although the Funes administration publicly acknowledged that El Salvador actively participated in the truce in 2013, the truce collapsed in 2014.[49] This occurred when the Salvadoran Supreme Court ruled that the appointment of the public security minister (who was the government’s truce plan designer) was unconstitutional since the Constitution banned military officers from filling any position in citizen security institutions.[50] The collapse of the gang truce had severe consequences. From 2014 to 2015, the homicide rate skyrocketed to 105 per 100,000 people, which was the highest 2015 homicide rate in the world.[51]

The world record homicide rate in 2015 was followed by a decline by 69 per 100,000 people from 2015 to 2019 (Figure 3).[52] In turn, the HDI rate only increased by 0.01 points during this same time period (Figure 1).[53] Two things can be inferred from this: 1) socioeconomic equality did not significantly increase from 2015 to 2019 and therefore did not contribute to the decline in homicide rates and 2) the effectiveness of the 2012 gang truce may have prompted the Salvadoran government to forge long-term covert agreements with gangs to decrease the homicide rate. El Faro and International Crisis Group investigations reveal that these unofficial agreements have endured until the present. According to the Salvadoran government, there has been a 60 percent drop in homicides since Nayib Bukele took office in June 2019.[54] Despite this impressive statistic, the significant decrease in the homicide rate may be rooted in the gangs’ decision to control violence as a result of a frail non-aggression pact with law enforcement entities.[55] The Bukele administration credits the plunging homicide rate with the effectiveness of the Territorial Control Plan, which is a robust strategy that embraces law enforcement in conjunction with violence prevention plans to combat crime and gangs.[56] Bukele’s Territorial Control Plan has a total budget of $575 million for 2019 to 2021, which is almost as twice as much as the funding for the 2019 Salvadoran military budget ($320 million).[57]

According to a Salvadoran investigative journalism organization, El Faro, Bukele made negotiations with MS13 leaders in order to reduce violence and homicides.[58] El Faro supported this claim by citing prison visit records and intelligence reports that revealed two members of Bukele’s administration (Carlos Marroquin, the Social Fabric Reconstruction Unit director, and prisons director Osiris Luna) negotiating with MS13 leadership on over a dozen occasions since June 2019.[59] The negotiations provided the gang members with quid pro quo benefits that included access to favorite foods and the unofficial annulment of mixing members of El Salvador’s three warring gangs in prison cells. This agrees with an InSight Crime expert’s assessment that when MS13 interacts with the Salvadoran state as a political actor, the gang focuses on fulfilling short-term needs (such as government related benefits outside of prison).[60] El Faro declared that the Salvadoran state was also providing gangs with social and economic programs in areas with a strong gang presence.[61] In return for this, MS13 leaders promised to decrease homicides and to support Bukele’s party (Nuevas Ideas) during the February 2021 legislative elections.[62] If Nuevas Ideas wins the 2021 legislative elections, laws that were unfavorable to the gang will be repealed and the gang will receive more benefits.[63] El Faro’s proposition that MS13 formed a homicide reduction pact with the Bukele administration is further supported by the decreased homicide rate began prior to Bukele taking office (and therefore prior to the Territorial Control Plan).[64] Additionally, a drop in homicides from January 2019 to April 2020 occurred not only in the 22 municipalities prioritized by the Territorial Control Plan, but also in the non-prioritized municipalities.[65] Hence, this strengthens the argument that the drop in homicides was not a result of the effectiveness of the Territorial Control Plan and police efforts.

According to a Salvadoran investigative journalism organization, El Faro, Bukele made negotiations with MS13 leaders in order to reduce violence and homicides.[58] El Faro supported this claim by citing prison visit records and intelligence reports that revealed two members of Bukele’s administration (Carlos Marroquin, the Social Fabric Reconstruction Unit director, and prisons director Osiris Luna) negotiating with MS13 leadership on over a dozen occasions since June 2019.[59] The negotiations provided the gang members with quid pro quo benefits that included access to favorite foods and the unofficial annulment of mixing members of El Salvador’s three warring gangs in prison cells. This agrees with an InSight Crime expert’s assessment that when MS13 interacts with the Salvadoran state as a political actor, the gang focuses on fulfilling short-term needs (such as government related benefits outside of prison).[60] El Faro declared that the Salvadoran state was also providing gangs with social and economic programs in areas with a strong gang presence.[61] In return for this, MS13 leaders promised to decrease homicides and to support Bukele’s party (Nuevas Ideas) during the February 2021 legislative elections.[62] If Nuevas Ideas wins the 2021 legislative elections, laws that were unfavorable to the gang will be repealed and the gang will receive more benefits.[63] El Faro’s proposition that MS13 formed a homicide reduction pact with the Bukele administration is further supported by the decreased homicide rate began prior to Bukele taking office (and therefore prior to the Territorial Control Plan).[64] Additionally, a drop in homicides from January 2019 to April 2020 occurred not only in the 22 municipalities prioritized by the Territorial Control Plan, but also in the non-prioritized municipalities.[65] Hence, this strengthens the argument that the drop in homicides was not a result of the effectiveness of the Territorial Control Plan and police efforts.

Instead, the decrease in homicide rates occurred as a result of an increased level of understanding and quiet dialogue between the Bukele administration and MS13.[66] The government agreed to allow MS13 to continue to control certain territories as long as violence is low. Since Bukele took office, there has also been a significant decrease in the number of clashes between gangs and security forces, which further highlights the likely existence of a non-aggression pact between gangs and the government.[67]

According to a panelist interviewed by an International Crisis Group sponsored event in July 2020, Bukele is attempting to maintain dialogue with gangs via local leadership to form medium and long-term agreements.[68] Bukele’s militaristic rhetoric (regarding law enforcement efforts against gangs) is likely used to veil government officials’ dialogue with gang members.[69] Ultimately, the Bukele administration is using punitive populist discourse in order to maintain public support for government anti-crime efforts.[70] Despite the likely establishment of non-aggression agreements between MS13 and the Salvadoran government, COVID 19 increased the volatility and unpredictability of the homicide rate in El Salvador due to the fact that a lack of extortion income (as a result of the lockdown) has put a strain on gangs. Abrupt slaughters attributed to MS13 in April 2020 illustrate the volatility of the gang’s commitment to decreasing violence.[71]

According to a panelist interviewed by an International Crisis Group sponsored event in July 2020, Bukele is attempting to maintain dialogue with gangs via local leadership to form medium and long-term agreements.[68] Bukele’s militaristic rhetoric (regarding law enforcement efforts against gangs) is likely used to veil government officials’ dialogue with gang members.[69] Ultimately, the Bukele administration is using punitive populist discourse in order to maintain public support for government anti-crime efforts.[70] Despite the likely establishment of non-aggression agreements between MS13 and the Salvadoran government, COVID 19 increased the volatility and unpredictability of the homicide rate in El Salvador due to the fact that a lack of extortion income (as a result of the lockdown) has put a strain on gangs. Abrupt slaughters attributed to MS13 in April 2020 illustrate the volatility of the gang’s commitment to decreasing violence.[71]

MS13’s Ability to Influence Election Results

MS13’s political power is not only derived from its ability to control the homicide rate, but also in its ability to serve as an electoral voting bloc and to control votes. MS13 has acquired de facto power in El Salvador, which is demonstrated by politicians negotiating with the gang for electoral support.[72] An independent researcher went on to reveal that the Salvadoran government returns the favor by reducing the number of arrests or detainments of MS13 members.[73] According to a US Southern Command Counter-Transnational Organized Crime Division expert, MS13’s political power is derived from the large size of its membership and dependents (spouses, children, etc.) as well as its ties with a large portion of the Salvadoran population, which can significantly impact electoral outcomes.[74] According to half of this article’s interview respondents, MS13 has obtained more political power from the early 2000s to the present.[75] An InSight Crime expert also assessed that MS13 has increased its pursuit of political power during the aforementioned period.[76] From the inception of the 2012 gang truce to the present, MS13 transformed from a street gang to a criminal organization with political and territorial control.[77]

MS13 utilizes three primary strategies to manipulate the electoral process, which include the following: charging political party candidates campaigning fees in gang-controlled neighborhoods; banning politicians or political parties that are perceived as enemies from campaigning in the gang’s areas; and financing mayors and local legislatures in order to position some of their own members into municipal strongholds.[78]

MS13’s increasing ability to control votes is rooted in its strong presence in a majority of Salvadoran municipalities and neighborhoods, which has made it more challenging for political parties to mobilize citizens in these areas.[79] This claim is supported by several experts. According to an InSight Crime expert, if MS13 agreed to obtaining neighborhood votes for a political party, opposition parties could not even access these neighborhoods.[80] In turn, another InSight Crime expert revealed that MS13 has accepted payment for blocking off campaigning areas of opposing candidates.[81] Additionally, this expert asserted that MS13 asks politicians for goods in exchange for access to the neighborhoods.[82] MS13’s ability to control votes is further supported by a US Embassy San Salvador Force Protection Detachment agent’s observation of MS13 members banning ARENA party members from handing out flyers.[83]

Because MS13 maintains a tight grip over the areas it controls, Salvadoran politicians approach MS13 members for votes in gang-controlled territories in exchange for passing legislation that would benefit the gang.[84] 2019 Attorney General investigations reveal that at least seven FMLN and ARENA politicians (former ministers, a presidential candidate, and the current mayor of San Salvador) allegedly forged deals with MS13 members to obtain electoral support.[85]

MS13’s ability to serve as an electoral voting bloc and to control votes blossomed during the 2014 presidential election. During this election, the ARENA and FMLN parties sought MS13 and Barrio 18’s support in exchange for money and less authoritarian government policies.[86] El Salvador’s former Interior Minister, Aristides Valencia, not only paid off MS13 via $10 million in micro-credit, but also sought to obtain the gang’s support during the second round of these elections.[87] ARENA leaders also offered identity cards and financial incentives in exchange for gang votes.[88]

MS13 members mobilized residents to vote for FMLN while simultaneously seeking to deter residents from voting for ARENA (the opposition party) prior to the first round of the 2014 elections.[89] According to a US Southern Command Counter-Transnational Organized Crime Division expert, MS13 mobilized between 4,000 and 6,000 votes for the FMLN candidate, Salvador Sánchez Cerén.[90] This expert deduced that Cerén would not have won the election without the votes of MS13 members and their dependents.[91] Despite this claim, it is difficult to determine the extent to which any given election is the product of voter intimidation due to the fact that negotiations between gangs and political actors are often covert.

Former gang leader testimony also revealed two important aspects of gang impact on electoral results. First, ARENA supporters were encouraged to not leave their homes during the day of the 2014 election. Second, MS13 confiscated voter identity cards from ARENA supporters in several neighborhoods.[92] This aligns with US Southern Command Counter-Transnational Organized Crime Division expert’s declaration that MS13 confiscated resident identity cards from non-FMLN supporters in order to reduce the number of ARENA votes.[93] This expert also revealed that MS13 sought to control votes by acting as poll workers during the election.[94]

While the 2014 presidential election was the most well-documented instance of MS13 manipulating the electoral process, gangs’ manipulation of electoral outcomes in El Salvador has allegedly occurred since the 2009 general election.[95] This has persisted until the 2019 Salvadoran presidential election. A US Embassy San Salvador Force Protection Detachment agent revealed that during this election, MS13 members circulated throughout San Miguel neighborhoods to collect resident identity cards to prevent residents from voting.[96]

MS13’s political power is also derived from its local power positions in marginalized neighborhoods.[97] This supports an InSight Crime expert’s observation, who revealed that MS13 controls votes through a sophisticated form of coercion such as the junta directiva.[98] The junta directiva is a community board that provides political representation for the neighborhoods. These boards have become the nexus between formal power (to liaise with municipality governments) and real power (the gang in some cases). According to this expert, MS13 members have belonged to junta directivas.[99]

MS13’s political power is also derived from its local power positions in marginalized neighborhoods.[97] This supports an InSight Crime expert’s observation, who revealed that MS13 controls votes through a sophisticated form of coercion such as the junta directiva.[98] The junta directiva is a community board that provides political representation for the neighborhoods. These boards have become the nexus between formal power (to liaise with municipality governments) and real power (the gang in some cases). According to this expert, MS13 members have belonged to junta directivas.[99]

In addition to the junta directiva, COVID 19 has inadvertently contributed to an increase in MS13’s political power. An InSight Crime expert revealed that COVID 19 has likely led to MS13 having more control over government resources.[100] This is expanded upon even further by another InSight Crime expert, who declares that COVID 19 has prompted MS13 to provide money to poor families during the pandemic. This has earned social capital for the gang (which translates into political power via its ability to influence votes).[101] This expert also stated that minimal police patrols as a result of the pandemic have enabled the gang to deepen its consolidation of territorial power.[102]

Conclusion

The Salvadoran government utilizes punitive populism in a two-pronged strategy: emphasizing authoritarian rhetoric and hardline law enforcement strategies against gangs while simultaneously forming pacts with gangs to keep the homicide rate low. The government uses these tactics to not only mask its covert pacts with gangs, but to also maintain public support. The government’s punitive populist strategies fortified MS13’s political power in a series of events: Mano Dura resulting in the strategic reorganization of MS13; the 2012 gang truce; the FMLN and ARENA parties seeking votes from the gang during the 2014 presidential elections; and MS13’s non-aggression pact with the Bukele administration.

The Salvadoran government’s criminalization and abandonment of the poor has also empowered MS13 politically. Because the government is failing to meet the needs of poor and marginalized communities (and MS13 members are a part of these communities), MS13 uses its control of the homicide rate as a political bargaining tool for fulfilling the gang’s needs.

The Salvadoran state’s employment of punitive populism has inadvertently led to the formation of official and unofficial agreements between MS13 and government officials. The Salvadoran state is easily vulnerable to corruption, inefficient, and incapable of confronting the gang.[103] As a result of this, dialogue between the gang and politicians is persistent due to the Salvadoran state’ inability to reacquire territorial control that MS13 exerts throughout the country.[104] This also sheds light on the Salvadoran government’s militarized and punitive populist approach towards law enforcement serve two functions: 1) to act as facades for appeasing the public demand for repressive anti-crime strategies and 2) to conceal the government’s backdoor deals with MS13 to reduce the homicide rate and/or provide political support in exchange for quid pro quo benefits for the gang.

The aim of this article was to explore the impact of the Salvadoran government’s employment of punitive populism on MS13’s political power. One of the most critical findings is that the Salvadoran state’s inability to confront and degrade MS13 effectively has led to an increase in the gang’s political capital. This inability is rooted in the Salvadoran government’s failure to significantly reduce socioeconomic inequality and its hardline approach to law enforcement. Because the Salvadoran government increased the wealth of the elite at the expense of the poor via neoliberal economic policies in the postwar environment, poor and marginalized communities were abandoned. Additionally, the government’s inability to equalize access to educational and employment opportunities has catalyzed MS13’s use of violence as a means of requesting entitlements that stem from a lack of these opportunities.

Although the Bukele administration seeks to flex its muscles against gangs via the Territorial Control Plan, this militarized anti-crime strategy is a paper tiger. A reduction in violence is rooted in the government’s willingness to concede to MS13’s demands (as opposed to the effectiveness of law enforcement). Furthermore, anecdotal evidence, descriptive statistics, and experts indicate that an increase in the Salvadoran government’s employment of punitive populism (specifically in the socioeconomic and military and law enforcement arenas) not only increases MS13’s political power, but enables it. On the basis of the findings generated by this article, it is concluded that the Salvadoran government’s preservation of elite power in conjunction with persistent abandonment and criminalization of the poor not only gave birth to MS13 as a social phenomenon, but also inadvertently equipped the gang with political power.

Notes

[1] Wood, William. “Punitive Populism: An Entry to the Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology.” 2014. In The Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology, edited by J. Mitchell Miller, 1. Wiley, 2014.

[2] Cruz, Jose Miguel. “Criminal Violence and Democratization in Central America: The Survival of the Violent State.” Latin American Politics and Society, No. 4 (Winter 2011): 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41342343

[3] Holland, Alisha. “RIGHT ON CRIME? Conservative Party Politics and Mano Dura Policies in El Salvador.” Latin American Research Review 48, No. 1 (Fall 2013): 44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41811587

[4] Osuna, Steven. “Transnational Moral Panic: Neoliberalism and the Spectre of MS-13.” Institute of Race Relations 61, No. 4 (February 2020): 15. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1177/0306396820904304

[5] Garni, Alisa and Frank Weyher. “Neoliberal Mystification: Crime and Estrangement in El Salvador.” Sociological Perspectives No. 4 (Winter 2013): 623. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/sop.2013.56.4.623

[6] Wade, Christine. “El Salvador: Contradictions of Neoliberalism and Building Sustainable Peace.” International Journal of Peace Studies No. 2 (Winter 2008): 15. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4185295

[7] Babineau, Kathryn, and Douglas Farah. “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras.” PRISM 7, No. 1 (September 2017): 59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26470498

[8] van der Borgh, Chris. “Government Responses to Gang Power.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies No. 107 (January 2019): 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26764790

[9] Cordova, Abby. “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador.” Latin American Research Review 54, No. 1 (Fall 2019): 204. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.387

[10] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 59

[11] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 59.

[12] Osuna, Steven, “Transnational Moral Panic: Neoliberalism and the Spectre of MS-13,” 10.

[13] Osuna, Steven, “Transnational Moral Panic: Neoliberalism and the Spectre of MS-13,” 10.

[14] The HDI calculates a composite score based on three components of human development: life expectancy at birth; access to educational opportunities (expected years of schooling and average years of schooling); and gross national income per capita (United Nations Development Program 2020). HDI is measured on a scale from 1 to 0. Furthermore, a low HDI score can be used to infer a low level of socioeconomic equality.

[15] Cruz, Jose Miguel. "Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador." In Global Gangs: Street Violence across the World, edited by Hazen Jennifer M. and Rodgers Dennis, and Venkatesh Sudhir, 128. University of Minnesota Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt6wr830.10.

[16] Chalk, Peter, et. al. “Counterinsurgency Transition Case Study: El Salvador.” In From Insurgency To Stability, 128. RAND Corporation, 2011.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg1111-2osd.12

[17] Chalk, Peter, et. al., “Counterinsurgency Transition Case Study: El Salvador,” 128.

[18] Chalk, Peter, et. al., “Counterinsurgency Transition Case Study: El Salvador,” 128.

[19] Cruz, Jose Miguel, "Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,"129.

[20] World Data Atlas. 2018. “El Salvador Human Development Index.” https://knoema.com/atlas/El-Salvador/Human-development-index

United Nations Development Program. 2019. “2019 Human Development Index Ranking.” http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/2019-human-development-index-ranking

[21] World Data Atlas, “El Salvador Human Development Index.”

United Nations Development Program, “2019 Human Development Index Ranking.”

[22] Insight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[23] Insight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[24] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[25] Independent Researcher, phone interview by the author, 30 November 2020.

[26] Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice 17, No. 6 (November 2007): 746. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25548280.

[27] World Data Atlas. 2019. “El Salvador-Military Expenditure in Current Prices.” https://knoema.com/atlas/El-Salvador/Military-expenditure

[28] World Data Atlas, “El Salvador-Military Expenditure in Current Prices.”

Holland, Alisha, “RIGHT ON CRIME? Conservative Party Politics and Mano Dura Policies in El Salvador,” 46.

[29] Holland, Alisha, “RIGHT ON CRIME? Conservative Party Politics and Mano Dura Policies in El Salvador,” 46.

[30] Holland, Alisha, “RIGHT ON CRIME? Conservative Party Politics and Mano Dura Policies in El Salvador,” 46.

[31] Independent Researcher, phone interview by the author, 30 November 2020.

[32] World Data Atlas, “El Salvador-Military Expenditure in Current Prices.”

[33] Hume, Mo, “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs,” 745.

[34] Hume, Mo, “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs,” 746.

[35] Hume, Mo, “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs,” 746.

[36] Cruz, Jose Miguel, “Criminal Violence and Democratization in Central America: The Survival of the Violent State,” 15.

[37] van der Borgh, Chris. “The Politics of Neoliberalism in Postwar El Salvador.” International Journal of Political Economy No. 1 (Spring 2000): 45.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40470765

[38] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[39] Cruz, Jose Miguel, "Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,"129.

[40] Cruz, Jose Miguel and Angelica Duran-Martinez. “Hiding Violence to Deal with the State: Criminal Pacts in El Salvador and Medellin.” Journal of Peace Research No. 2 (March 2016): 206. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43920009

[41] Cruz, Jose Miguel and Angelica Duran-Martinez. “Hiding Violence to Deal with the State: Criminal Pacts in El Salvador and Medellin,” 197.

[42] The World Bank. 2018. “Intentional Homicides (Per 100,000 People) – El Salvador.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/VC.IHR.PSRC.P5?locations=SV

US Department of State Overseas Security Advisory Council. 2020. “El Salvador 2020 Crime & Safety Report.”

[43] Cruz, Jose Miguel and Angelica Duran-Martinez. “Hiding Violence to Deal with the State: Criminal Pacts in El Salvador and Medellin,” 205.

[44] Cruz, Jose Miguel and Angelica Duran-Martinez. “Hiding Violence to Deal with the State: Criminal Pacts in El Salvador and Medellin,” 205.

[45] The World Bank. “Intentional Homicides (Per 100,000 People) – El Salvador.”

US Department of State Overseas Security Advisory Council. “El Salvador 2020 Crime & Safety Report.” https://www.osac.gov/Country/ElSalvador/Content/Detail/Report/b4884604-977e-49c7-9e4a-1855725d032e

[46] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 60.

[47] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[48] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 60.

[49] Ivan Briscoe, Timo Peeters, and Gerard Schulting. 2013. “Truce on a Tightrope: Risks and Lessons from El Salvador’s Bid to End Gang Warfare.” Clingendael Institute. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep05313

[50] Cruz, Jose Miguel and Angelica Duran-Martinez. “Hiding Violence to Deal with the State: Criminal Pacts in El Salvador and Medellin,” 206.

[51] International Crisis Group. 2020. “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.” https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america caribbean/central-america/el-salvador/81-miracle-or-mirage-gangs-and-plunging-violence-el-salvador

[52] The World Bank. “Intentional Homicides (Per 100,000 People) – El Salvador.”

US Department of State Overseas Security Advisory Council. “El Salvador 2020 Crime & Safety Report.”

[53] World Data Atlas, “El Salvador Human Development Index.”

United Nations Development Program, “2019 Human Development Index Ranking.”

[53] Cruz, Jose Miguel, "Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,"129.

[54] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[55] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[56] Steven Dudley and Alex Papadovassilakis. 2020. “How El Salvador President Bukele Deals with Gangs.” https://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/el-salvador-president-bukele-gangs/

[57] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[58] Anna-Catherine Brigida, “El Salvador’s Government Cut Deals with MS-13 Gang in Bid to Reduce Killings, Report Says,” The Americas, September 5, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/el-salvador-gangs-violence/2020/09/05/8fb8734e-eee3-11ea-bd08 1b10132b458f_story.html

[59] Anna-Catherine Brigida, “El Salvador’s Government Cut Deals with MS-13 Gang in Bid to Reduce Killings, Report Says.”

[60] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[61] Steven Dudley and Alex Papadovassilakis, “How El Salvador President Bukele Deals with Gangs.”

[62] Anna-Catherine Brigida, “El Salvador’s Government Cut Deals with MS-13 Gang in Bid to Reduce Killings, Report Says.”

[63] Gomez, Maria Luisa. October 14, 2020. “La influencia politica de las maras en El Salvador.” Instituto Español de Estudios Estrategicos.

http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2020/DIEEEA32_2020LUIPAS_marasSalvador.pdf

[64] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[65] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[66] InSight Crime Experts, phone interviews by the author, 6 and 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[67] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[68] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[69] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[70] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[71] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[72] Gomez, Maria Luisa. “La influencia politica de las maras en El Salvador.”

[73] Independent Researcher, phone interview by the author, 30 November 2020.

[74] US Southern Command Counter Transnational Organized Crime Division Expert, phone interview by the author, 4 November 2020.

[75] US Embassy San Salvador Force Protection Detachment Agent, phone interview by the author, 5 November 2020. InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. Independent Researcher, phone interview by the author, 30 November 2020.

[76] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[77] Gomez, Maria Luisa. “La influencia politica de las maras en El Salvador.”

[78] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 64.

[79] Cordova, Abby, “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador,” 205.

[80] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[81] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[82] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[83] US Embassy San Salvador Force Protection Detachment Agent, phone interview by the author, 5 November 2020.

[84] Farah, Douglas. “Central American Gangs: Changing Nature and New Power.”

Journal of International Affairs 66, No. 1 (Fall 2012): 63.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24388251

[85] International Crisis Group, “Miracle or Mirage? Gangs and Plunging Violence in El Salvador.”

[86] Cordova, Abby, “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador,” 206.

[87] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 62.

[88] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 62.

[89] Cordova, Abby, “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador,” 206.

[90] US Southern Command Counter Transnational Organized Crime Division Expert, phone interview by the author, 4 November 2020.

[91] US Southern Command Counter Transnational Organized Crime Division Expert, phone interview by the author, 4 November 2020.

[92] Cordova, Abby, “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador,” 206.

[93] US Southern Command Counter Transnational Organized Crime Division Expert, phone interview by the author, 4 November 2020.

[94] US Southern Command Counter Transnational Organized Crime Division Expert, phone interview by the author, 4 November 2020.

[95] Cordova, Abby, “Living in Gang-Controlled Neighborhoods: Impacts on Electoral and Nonelectoral Participation in El Salvador,” 206.

[96] US Embassy San Salvador Force Protection Detachment Agent, phone interview by the author, 5 November 2020.

[97] van der Borgh, Chris, “Government Responses to Gang Power,” 3.

[98] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[99] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[100] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 6 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[101] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[102] InSight Crime Expert, phone interview by the author, 24 November 2020. InSight Crime is a non-profit journalism and investigative organization specialized in organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. The organization has offices in Washington, D.C. and Medellín, Colombia. https://insightcrime.org

[103] Babineau and Farah, “The Evolution of MS13 in El Salvador and Honduras,” 70.

[104] Ávalos, et. al., “Symbiosis: Gangs and Municipal Power in Apopa, El Salvador.”

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2021 Quixote Globe

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2021 Quixote Globe