The EU has always been a fervent defender of noble causes, such as Human Rights, the freedom of oppressed peoples, and the Green Deal. The grandiloquence of its discourse has always been applauded by governments and populations all over the world, nobody disputes the humanist quality of the values they defend, and those proclaimed values are a political and social guide for the governments of the world. Even when the discourse is incongruent with reality. As is happening with the Ukraine issue.

Certainly, the EU member countries uphold this set of values, and their populations are proud that they do. The problem comes when the EU defends values or political positions that are not aligned with the supreme value of improving the lives of its citizens, and when the EU defends positions aligned with foreign interests opposed to its noble causes. One of the frictions between the discourse of political independence and its geopolitical alliances has its epicenter in energy policy. Specifically, the problem came from the distribution of Russian gas. Not from the dependence that the media talk about, but the distribution.

In 2004 the EU imported 40% of its natural gas from Russia, and it did so through Ukraine. This country was a key player in the transit of gas to Europe, but it was unable to pay for the gas it transported, which led to the accumulation of unsustainable debts. This situation had been cyclical since the early 1990s, with Ukraine unable to meet its economic obligations, straining Russia's relations with its European customers. The situation was resolved once in 2004 when Gazprom approved a loan to the Ukrainian state-owned company Naftogaz to pay the accumulated debts.

The agreement ensured distribution for five years, after which the same situation arose again. This time the situation was settled in an arbitration court in Stockholm, and Ukraine had to pay a debt it claimed was unfair. The response of Ukraine's Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko was to sue Gazprom in U.S. courts. Friction over energy transport through Ukraine can be seen as having shaped the political conflict agenda in Ukraine, and the fact that Ukraine sought judicial protection in the U.S. is an indicator that balances the axis of Ukraine's allies. Ukraine's interests were hereon defended in the US.

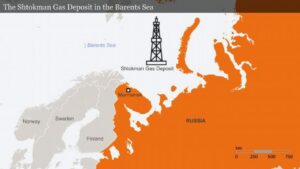

Even so, the conflicts between Russia and Ukraine did not cease; large quantities of gas were, somehow, disappearing, multi-million debts were accumulating, and it was increasingly questionable whether Ukraine was a safe country for the transit of gas to Europe. The main European energy problem stemmed from the impossibility of secure transportation of Russian gas, and given the new Ukrainian alliances, it is very likely that this situation was caused by third parties with divergent interests to the Europeans and the Russians. Russia was also rethinking its alliance system and decided to start on its way to becoming an energy power on its own. In 2006 Gazprom announced that it would build the world's largest offshore gas field, Shtokman, without partners. The Russian energy market pie left out all other global players. It was an unmistakable sign of Russian determination to face foreign interference.

In 2009, the crisis was repeated, and it was then that many voices arose, worrying about Russia's energy dependence and Ukraine's unreliability as a partner. The new crisis made clear Russia's dependence on Ukraine as a transit country to Europe. Evidently, the solution on the Russian side was to create new distribution routes, while for Europe the solution was to diversify energy sources. While political and social disengagement operations against Russia were taking place in Ukraine, the former began to build the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline in 2010, and in 2018 construction began on Nord Stream 2. At that time, Europe assumed that Ukraine would comply with the supply agreements it had signed in the Energy Charter Treaty, regardless of its relationship with Russia. That’s all the EU did.

In 2009, the crisis was repeated, and it was then that many voices arose, worrying about Russia's energy dependence and Ukraine's unreliability as a partner. The new crisis made clear Russia's dependence on Ukraine as a transit country to Europe. Evidently, the solution on the Russian side was to create new distribution routes, while for Europe the solution was to diversify energy sources. While political and social disengagement operations against Russia were taking place in Ukraine, the former began to build the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline in 2010, and in 2018 construction began on Nord Stream 2. At that time, Europe assumed that Ukraine would comply with the supply agreements it had signed in the Energy Charter Treaty, regardless of its relationship with Russia. That’s all the EU did.

As we have seen, to understand the current energy conflict, it is necessary to know the different variables that compose it and their intersections. The line from Russia's energy to Germany's industry had a noise signal that contaminated communication. Ukraine was the strategic stage on which to develop political operations to break the Moscow-Berlin axis. In the summer of 2020, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas declared that European energy policy was the business of Europeans, at least of Germans. The German politician was fully convinced of the solid relations between his country and Russia. Donald Trump thought differently. The United States was concerned that the Berlin-Moscow axis was taking hold, and the clean and cheap energy coming from Russia was endangering the geopolitical interests of the American country; on the one hand, Europe was no longer a captive customer of American energy, on the other a multipolar zone of influence was being created to the detriment of the unipolar hegemony the USA had abused for decades. The struggle against Europe's political and energy sovereignty began with sanctions against the companies involved in the NordStream II project. The United States had to defend its hegemonic status, and the country had still great influence in European politics.

Since the start of the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, it is very common to open the newspaper and read about the European energy crisis, the conflict in Ukraine, how Putin weaponizes energy, about how Putin commits war crimes. The media sells the current crisis as having arisen spontaneously in February of this year. One day, Vladimir Putin woke up in a bad mood and decided to invade the neighboring country. Those of us who have been analyzing geopolitical issues for years know the timeline of events. Those of us who pay the electricity bill remember how the price of electricity has been rising steadily for more than a year.

Since the start of the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, it is very common to open the newspaper and read about the European energy crisis, the conflict in Ukraine, how Putin weaponizes energy, about how Putin commits war crimes. The media sells the current crisis as having arisen spontaneously in February of this year. One day, Vladimir Putin woke up in a bad mood and decided to invade the neighboring country. Those of us who have been analyzing geopolitical issues for years know the timeline of events. Those of us who pay the electricity bill remember how the price of electricity has been rising steadily for more than a year.

In Spain we remember how our president, Pedro Sanchez, announced a new electricity bill structure, we remember how we were told that to save money we had to put the washing machine on at three in the morning. After a year of doing so, prices are still soaring and European leaders have failed to reach an agreement on how to solve the energy problem. The energy crisis did not start in February of this year, it had already been provoked by the political power of the EU a year earlier.

Since the conflict began, the EU is defending a geopolitical model that is counterproductive to the well-being of its population, its industry, and its position on the geopolitical map. The situation in Ukraine has led the unelected EU leaders to compromise the social welfare enjoyed by its inhabitants. The closest they almost agreed was about the gas cap price, but they didn’t. The greatest unanimity the EU leaders have reached is to agree that energy demand must be lowered and supply regulated, which translates into less comfort in homes and less production in industries.

Trying to understand the EU's energy policies from a rational point of view is complicated, so formal logic must be replaced by informal logic, critical thinking. If the sanctions imposed against Russia do not mitigate the armed conflict, and do not mitigate the energy crisis (but rather aggravate it), but continue to be imposed, it is possible that the sanctions are not intended to end either the crisis or the conflict. Getting clean and cheap energy from Russia is considered an unacceptable dependency as well as a contribution to war crimes. But enduring dependence on dirty and expensive energy is an act of freedom and independence. George Orwell´s doublespeakspeak never made so much sense.

The EU, for years, had approved a roadmap that would shift energy consumption towards clean energy sources. The EU Green Deal set the year 2050 as the year when Europeans would be eco-sustainable, energetically speaking. Not only is domestic energy consumption to be green, but the aim is to have green steel in the automotive industry in the coming years. EU is on the Green fever. The conflict in Ukraine is serving to accelerate the Green Deal and to limit Europe's industrial capacities by imposing unbearable energy prices. The energy policies adopted by Europe are a catalyst for the dismantling of the continent's economic system.

For this reason, it is perfectly understandable that Germany is seeking a rapprochement with the Eurasian bloc. To scream out against a conflict in which thousands of human beings are suffering is a moral obligation, and is not inconsistent with reality. But avoiding the suffering of human beings is not the real reason for the EU's current political positions.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2022 Quixote Globe

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2022 Quixote Globe

Europe is on the verge of a big decision. It will either defend its own interests and make an acceptable deal with Russia, or it will act as a satellite of the United States and make its people pay a great economic price.

I do not accept the US having a say in how EU-Russia relations will be. Is sabotage to the north stream pipeline in the EU’s interest or not? We can conclude by looking at the bills we pay.

Very important arguments… The article points out the real reasons of Europe’ energy crisis and how can they find a way out from this crisis.