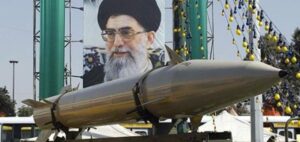

Will Biden retake the Iran nuclear deal?

Will Biden retake the Iran nuclear deal?

In the penultimate year of his presidential term, Barack Obama succeeded in getting Iran to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Thus, on April 4, 2015, the framework agreement on the Iranian nuclear program was signed in Vienna, a text of more than one hundred pages - with five annexes - between the government of Tehran and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (USA, China, Russia, United Kingdom and France) plus Germany, known as the P5+1. Subsequently, on July 14 of the same year, the parties agreed on the final plan.

It was the culmination of an initial agreement reached in November 2013, personally pushed by Obama, perhaps feeling the political need to justify the Nobel Peace Prize he had been awarded in October 2009, practically pre-emptively as he had barely begun to warm the chair in the Oval Office.

The reality was that, until then, he had failed to deliver on any of the three reasons for which he had been so generously awarded the prize: nuclear disarmament, peace in the Middle East and climate change.

But if Obama had thought he could fool the Iranians, he was obviously wrong. Heirs to one of the world's most ancient cultures, in which foreign deception is imprinted in their genes, endowed with ancestral cunning and shrewdness, the Iranians managed to turn the treaty in such a way that it was as favorable as possible to them, even if the US president publicized it in a very different way, showing himself proud of having achieved a theoretical milestone to guarantee world peace, by avoiding the danger of nuclear proliferation.

It is true that, according to the agreement, Iran undertook, for ten years, to reduce the number of centrifuges in operation from some 19,000 to 5,060, and to use only the R-1 type, prohibiting the R-2, and even more modern models, which are between five and ten times faster. On the other hand, the centrifuges were to be concentrated in Natanz, to facilitate inspections. And during the same period of time, the maximum level of uranium enrichment allowed would be 3.67% (the usual for industrial use; for military applications it exceeds 80%). Likewise, and for 15 years, stocks and storage of depleted uranium were limited to 300 kilograms. At the same time, with regard to plutonium, the Arak facilities were to be redesigned, the core of which was to be destroyed or removed from the country. Finally, Iran was to grant access to all nuclear facilities, mines and mills, and centrifuge production centers.

It is true that, according to the agreement, Iran undertook, for ten years, to reduce the number of centrifuges in operation from some 19,000 to 5,060, and to use only the R-1 type, prohibiting the R-2, and even more modern models, which are between five and ten times faster. On the other hand, the centrifuges were to be concentrated in Natanz, to facilitate inspections. And during the same period of time, the maximum level of uranium enrichment allowed would be 3.67% (the usual for industrial use; for military applications it exceeds 80%). Likewise, and for 15 years, stocks and storage of depleted uranium were limited to 300 kilograms. At the same time, with regard to plutonium, the Arak facilities were to be redesigned, the core of which was to be destroyed or removed from the country. Finally, Iran was to grant access to all nuclear facilities, mines and mills, and centrifuge production centers.

Ultimately, the development of the nuclear program was contained to 10 to 15 years, with Iran's explicit commitment to non-proliferation, thus limiting the nuclear threat and the options for military attack.

What might at first appear to be a great success, in reality concealed important ambiguous points or points of dubious application. To begin with, no reference was made to what was to be done with the centrifuges that would cease to operate. On the other hand, it authorized the operation of 1,044 high-tech centrifuges at Fordow, for scientific purposes (having to use elements other than uranium), for eight years, which made it possible that, in the event of a breach of the agreement, they could be immediately reused for the nuclear program. Although the amount of uranium stockpiles was reduced - but not eliminated - there was no obligation to remove the remaining uranium from the country. And perhaps most importantly, considered by the Iranians as a great triumph: the advanced Iranian missile system is not contemplated in any way, allowing them to continue to develop their delivery vehicles.

With all this, the real conclusion is that the entire nuclear infrastructure was kept intact, with no guarantee or mechanism for early detection of non-compliance with the agreement. Thus, it was left to the will of the Iranians to have a nuclear program in fortified locations.

Moreover, the fact that in a few years Iran could return to a fully operational nuclear program without any technological limitations, made Iran a de facto "virtual" nuclear power, as it could resume the program in a very short period of time.

As if that were not enough, both the excessive dependence on the good will of the parties for the implementation of the agreement and the dubious procedure in the event of its violation or non-compliance were called into question. Precisely when negotiating with a country, Iran, which had shown itself to be a great expert in concealment and in accumulating small and successive breaches.

All of the above could be summarized as follows: if Iran decided not to respect the agreement, it would have at its disposal a nuclear program of industrial dimensions installed in fortified sites. Even if it respected the agreement, after 10/15 years it would have a fully operational nuclear program and without any technological, enrichment level or facility limitations. There was no guarantee or mechanism for early detection of non-compliance with the agreement.

As it is, Donald Trump's misgivings are understandable, once in office, he was informed by his advisors of the lesser-known details.

But there was something else. Although time has partially erased our memory, we must make an effort to remember that, as soon as the agreement was signed, Europe's view of Iran changed rapidly. Until then, and since Khomeini carried out his revolution and seized the reins of power in 1979, the image of Iran as the focus and origin of all evil had been conveyed to us with great insistence. This generated a deep animosity towards the Persian country. Suddenly, however, it became desirable. Many high-ranking European officials traveled to Iran to try to close big deals. It was no wonder. Iran, in a very bad economic situation as a result of the sanctions and embargoes it had been suffering for years - imposed for years by the US - was waiting for the release of tens of billions of dollars that had been frozen for decades. With that money, it hoped not only to revive its ailing economy, but also to acquire products and means, build facilities and set up urgently needed industries. And in the face of these enormous business prospects, some of Europe's leading politicians jumped at the chance to get a piece of the pie. Needless to say, Iran was delighted to do business with the European countries - less so with the UK - and to leave the US completely out of the picture. The wounds of the 1953 coup d'état -which ousted the nationalists from power and imposed the Shah as ruler, and in which the British and US intelligence services played a major role- and the aftermath of the 1979 revolution are still open. Thus, pre-contracts began to be signed for the purchase of European aircraft, vehicles and a multitude of other products.

But there was something else. Although time has partially erased our memory, we must make an effort to remember that, as soon as the agreement was signed, Europe's view of Iran changed rapidly. Until then, and since Khomeini carried out his revolution and seized the reins of power in 1979, the image of Iran as the focus and origin of all evil had been conveyed to us with great insistence. This generated a deep animosity towards the Persian country. Suddenly, however, it became desirable. Many high-ranking European officials traveled to Iran to try to close big deals. It was no wonder. Iran, in a very bad economic situation as a result of the sanctions and embargoes it had been suffering for years - imposed for years by the US - was waiting for the release of tens of billions of dollars that had been frozen for decades. With that money, it hoped not only to revive its ailing economy, but also to acquire products and means, build facilities and set up urgently needed industries. And in the face of these enormous business prospects, some of Europe's leading politicians jumped at the chance to get a piece of the pie. Needless to say, Iran was delighted to do business with the European countries - less so with the UK - and to leave the US completely out of the picture. The wounds of the 1953 coup d'état -which ousted the nationalists from power and imposed the Shah as ruler, and in which the British and US intelligence services played a major role- and the aftermath of the 1979 revolution are still open. Thus, pre-contracts began to be signed for the purchase of European aircraft, vehicles and a multitude of other products.

When Trump was also informed of this, his businessman's instincts tipped him off. He did not understand how it could have been so naive as to release such large sums of money and that Tehran intended to spend it in other countries, leaving out the US, which had been the real architect of the nuclear agreement.

As if that were not enough, Trump sought to give a nod to Israel, a strategic country with which he intended to strengthen relations weakened during the Obama Administration, and which continued to see Iran as a threat, direct and indirect, to its national security, starting with its support for Hamas and continuing with its increasingly powerful presence in neighboring Syria.

Thus, finally, in May 2018, Donald Trump withdrew his country from the agreement and reinstated sanctions on Iran, in the hope (unsuccessfully) of ending its economic suffocation and that it would be the Iranian people themselves who would rise up against their leaders and bring about a change of government, aided by indirect actions propitiated by the US intelligence services and those of some of their traditional allies.

But Iran is a tough nut to crack, as it has been proving for years. Not only has it not been intimidated, but it has been gaining strength in the Middle East. It has created its own "golden arc of resistance", with loyal allies, ranging from Yemen to Syria, passing through Iraq, and not forgetting Afghanistan. With the implicit support of other powers, such as China, it has continued to partially export its resources and to circumvent sanctions, albeit with great hardship.

As far as the nuclear issue is concerned, missile development has been remarkable. And that is not all. As soon as the US withdrew from the agreement, Iran began to enrich uranium, reaching 4.5%. No sooner had this year 2021 begun than Tehran announced that the Shahid Almohammadi complex, belonging to the Fordow subway nuclear facility, had begun the process of enriching uranium to 20%, far exceeding the agreed 3.67%. Although still far from the 80% at which military use begins, it is an outstanding gesture, not to say a clear challenge to the signatory countries of the agreement.

As far as the nuclear issue is concerned, missile development has been remarkable. And that is not all. As soon as the US withdrew from the agreement, Iran began to enrich uranium, reaching 4.5%. No sooner had this year 2021 begun than Tehran announced that the Shahid Almohammadi complex, belonging to the Fordow subway nuclear facility, had begun the process of enriching uranium to 20%, far exceeding the agreed 3.67%. Although still far from the 80% at which military use begins, it is an outstanding gesture, not to say a clear challenge to the signatory countries of the agreement.

This is the scenario that Joe Biden "the peacemaker" now finds himself in. A thorn that can easily get stuck in his side. If he resurrects the nuclear agreement, nothing guarantees Iranian "loyalty". As if that were not enough, this fact would indispose him with Israel. And if he manages to recover it fully, he could find himself once again in the position of having to see how the Iranians buy European products and ignore the U.S. There is no doubt that his partners in Europe will encourage him to recover the agreement, with their eyes set on the foreseeable business, especially at a time when the economy of the Old Continent, due to the Covid pandemic, is strongly affected.

Obviously, one solution would be - as Trump has already tried - for the Iranians to guarantee that American companies would be the ones to benefit. But this would be detrimental to the Iranian government, as its people would not take it on without open opposition.

If these and other issues make Biden reconsider reviving the nuclear agreement, he would be renouncing one of his main electoral promises. It is not something that should surprise us, as it is the most common among politicians, but his image would be called into question. And that is what happens when you get too dignified and promise too much. Although he always has the resource, as we see with excessive and shameful frequency, of saying that he did not have enough information, and that only now, when he knows all the details, he can take the pertinent decision. In the case of Biden this trickery is more difficult to admit, taking into account that he is not a newcomer to politics -which was the case with Trump-, since half a century of experience weighs on his shoulders, including eight years as vice-president.

It will be interesting to see how Biden applies his "do-gooderism" strategy to this case. He undoubtedly runs the risk of being bullied by the Iranians, as they did with Obama.