A country’s politics, its military doctrine itself and that of their adversary, the geography of the theater of operations, the international environment, the assigned mission, and the commander’s prejudices comprise a series of variables that directly influence military operations and their outcomes. Through the historical context that led to the battle of Dien Bien Phu, we will follow the actions that led to General Henry Navarre’s defeat and examine how the factors mentioned above influenced his decisions.

INDOCHINA AND THE COLONIAL POWERS BEFORE 1945

THE EUROPEAN COLONIZATION

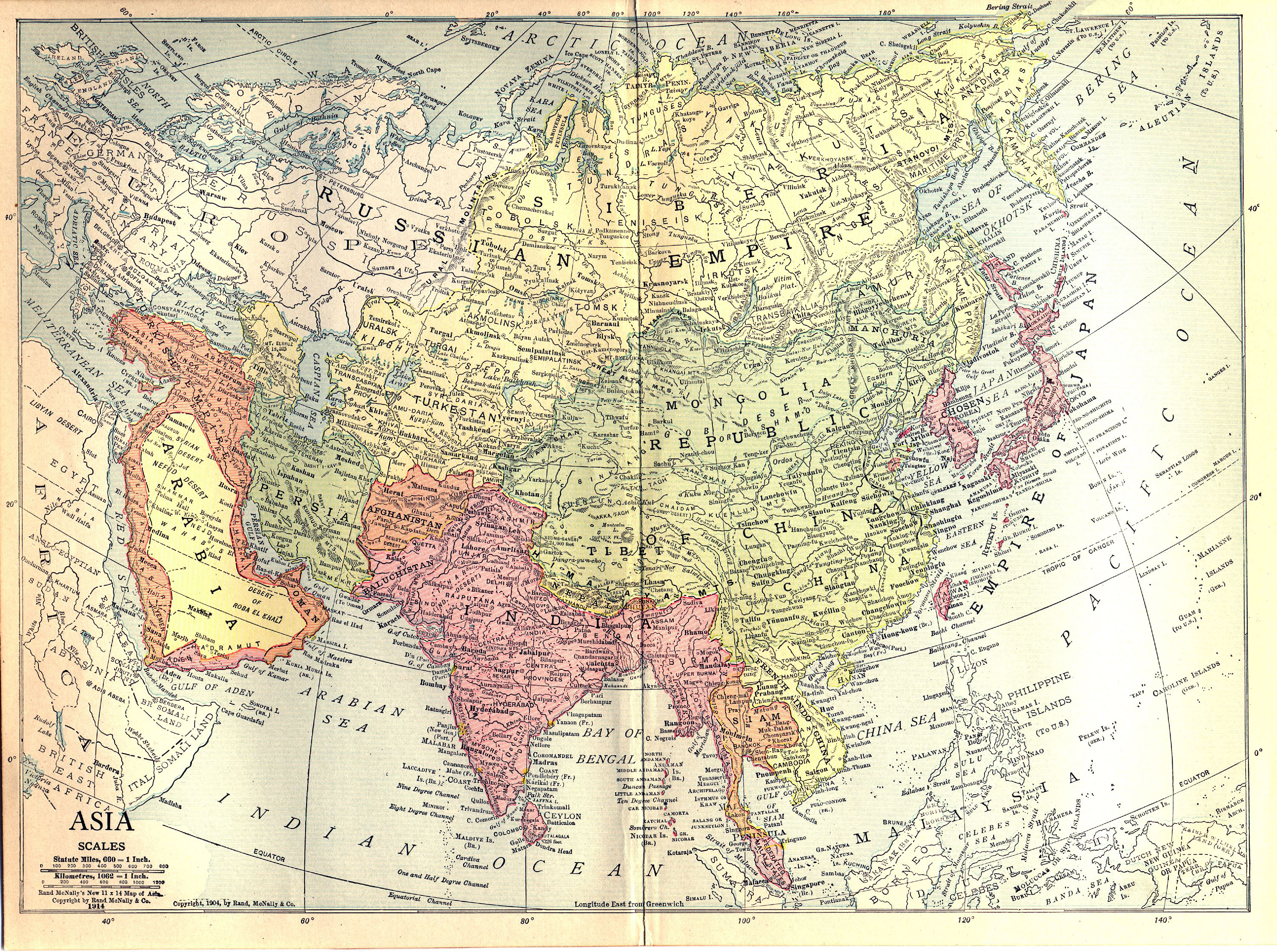

When Europeans expanded across the globe in search of resources, the Indochina region did not escape their search for wealth. The Portuguese, first to arrive in the region, seized the Malacca peninsula in 1511, conquering East Timor. Subsequently, the Spanish took the Philippines, seizing Cebu in 1565 and Luzon in 1571. The Dutch established a settlement on the coast of Malaysia in Malacca, eventually occupying the East Indies. On the other hand, the British obtained concessions in Penang in 1791 and in Singapore in 1819, securing the transit of their ships and later annexing Burma between 1824 and 1886, managing to protect access to India through the East. Later they advanced on the Malacca peninsula which, offered them control of the only routes that join the Indian and Pacific Oceans, with clear intentions of denying them to the French. Between 1859 and 1899, France occupied Laos, Cambodia and present-day Vietnam. The United States was the last to join the region, occupying the Philippines after defeating the Spaniards in 1898. Thailand was not occupied and served as a buffer state to avoid direct confrontations between the English and the French.

The new settlers benefited to the detriment of the local population and economy. This slowly led to growing opposition against the occupiers, who in turn, aggressively stifled any kind of uprising. The opposition towards the colonial powers became more prevalent as the subjugated populations became aware of the concept of nationalism and claimed the right to govern themselves.

This consciousness was strengthened starting in the 1920s by the principles of communism, both in theory (Mao Tse-tung) and practice (Ho Chi Minh). The latter led the Youth Revolutionary League, from which the Indochinese Communist Party was born in 1929. There were already communist parties in the region, who were the first clandestine political opposition against the colonial rulers. However, they were not powerful as their efforts were violently stifled by the occupiers, and at best, were only able to maintain status quo, due to the lack of a unifying element as well as the attitude of the settlers, as is the case of the U.S. by granting independence to the Philippines.

THE INTERVENTION OF THE JAPANESE EMPIRE.

After the military triumphs against China (1894-1895) and Russia (1904-1905), Japan undertook an expansionist policy to achieve its prosperity. This policy led to the occupation of Korea in 1910 and the attacks on Manchuria in 1931 and China in 1937. The sustainment of these operations was affected by Japan’s lack of resources and within that framework we can glimpse into the decision to attack the US and later the colonial possessions of Europeans and Americans in Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Japan had as its objective the creation of a "Co-prosperity Sphere in Greater Central Asia" incorporating the Philippines, Malaya, Borneo and the East Indies. The objective was that, under their control, these countries would provide the necessary raw materials for their armed forces, thus achieving - despite political opposition - a position of strength such that Europeans and Americans would be dissuaded from attacking them. Japan's surprise participation in World War II, through the attack on "Pearl Harbor" on December 7, 1941, coupled with the fact that the European powers were engaged against Germany, allowed Japan to succeed militarily in Southeast Asia.

American forces were defeated in Guam and the island of Wake and the British in Hong Kong, enabling the projection of forces that allowed the fall of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula on February 15, 1942, and the subsequent defeat of the Dutch Navy on February 27 at the Battle of the Java Sea, who surrendered the Dutch East Indies on March 9.

The US lost the Philippines on May 6, while the British withdrew from Burma and Thailand and French Indochina fell under the influence of Japan. This Japanese advance, which in less than 6 months consolidated the "Joint Greater Co-prosperity Sphere of Greater East Asia", dealt a devastating blow to colonial prestige, taking away the myth of invincibility and encouraging anticolonial movements in the region.

Japan offered the colonies the possibility of independence under their own rules, which in the long run became the substitution of one colonizer for another that was determined to extract all the resources of the region. However, this allowed nationalist groups to gain political capital.

In Indochina, Emperor Bao Dai did not represent any political group and cooperated with the Japanese. While, on the other hand, nationalists, who had popular support, started in 1941 to organize an armed opposition to the Japanese regime, receiving help from the Allies, especially the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Guerrillas against the Japanese were supported by the British and the US, and even augmented their armed forces, as in the case of the Philippine nationalist guerrilla forces.

In Vietnam, it was the communists who took the initiative, with the creation of the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoy (League for the Independence of Vietnam, commonly abbreviated as Viet Minh), in May 1941 under the guidance of Ho Chi Minh, receiving military support from the OSS. However, the Viet Minh placed their focus on capturing popular support and not on attacking the Japanese.

CONSEQUENCES OF WORLD WAR II

The Second World War produced a break in the history of Southeast Asia. In a period of four years, the colonial regimes not only lost the prestige they had in the eyes of the locals, but also the Japanese occupation triggered the demands for independence of the entire region, vigorously increasing the nationalist movements and eliminating the possibilities of the colonialist countries to resume control.

Although the Americans had openly stressed decolonization and political freedom, the countries prepared themselves for the recovery of their Asian colonies, making the armed conflict inevitable.

PARTIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The expansion of European countries in search of resources led to the colonization of Indochina by France starting in 1859. The pressure exerted by the French on the local population to extract resources created the desire for their independence. This desire for independence was strengthened by the principles of communism and culminated in the Youth Revolutionary League, which gave rise to the Indochinese Communist Party in 1929, led by Ho Chi Minh.

The fall of French Indochina into Japanese hands in 1941 was only a change of the dominant country that favored the consolidation and determination of the Vietnamese people to achieve independence.

With the defeat of Japan in 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, supported by the OSS. However, this did not stop the Europeans to begin to recover their lost colonies.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS – THE RETURN TO FRANCE

As Operation Overlord was carried out by the Allies, on June 6, 1944, France, led by General Charles de Gaulle, tried to consolidate and unify its government which was dispersed in different French civilian and paramilitary entities. By the end of 1944, France had a field army of 230,000 men (the 1st Army under General Lattre and the 2nd Armored Division under General Leclerc), with equipment leased from the Americans; and sovereignty forces (those destined to preserving control of the colonies) composed of 150,000 men, a fleet of more than 300,000 tons, and 500 aircraft totaling 30,000 airmen (armed and trained by the US).

Since 1940 a status quo was maintained with regards to the colonial forces deployed in Indochina, after General Catroux, at the head of the General Government of Indochina, signed a convention in Tokyo that respected French authority over Indochinese territory in exchange for military facilities, since Japan was otherwise engaged against China. At the beginning of 1945, the Japanese visualized their future defeat and decided to facilitate Ho Chi Min’s plans for the independence of the colonies. Thus, on March 9th, Japanese troops attacked the French garrisons, destroying them completely, and forcing the surviving forces to flee northwards to join the Chinese forces. The immediate consequence of this action was the disappearance of the Indochinese administration and the clandestine penetration of revolutionary gangs.

After the surrender of Japan, Ho Chi Minh seized Hanoi on August 19th, and after the abdication of Bao Dai, on September 2nd, constituted the provisional government of the Republic of Vietnam favored by elements of the American secret services. During that month the Japanese forces stationed in Indochina surrendered, to the south of the 16th parallel to the British forces and to Chinese forces on the north. France reacted by organizing, albeit slowly, a colonial force of two divisions in the south of the country to recover the territory, supported by the U.S., who provided weapons, further augmented by its own naval forces in October under the command of the General Leclerc.

During 1946, France and Ho Chi Minh signed agreements and held meetings in Vietnam and France. However, talks between the parties ended after a surprise attack by the Viet Minh forces on December 19th, 1946, which were repelled and led to the start of a guerrilla war by the Vietnamese. In terms of politics, 1946 was a turbulent year in France, as on January 20th, General De Gaulle left the government on in the hands of the Constitutional Assembly, while a new constitution that would give shape to the IV Republic was being developed and subsequent the appointment of Vincent Auriol as president of France on January 16, 1947.

During 1947 France’s interests leaned towards the events in its Moroccan colony. The latter showed clear signs of wanting to become independent and, although France intended the same thing, it considered the reaction of the local government premature. This occurred at a time in which the French armed forces were almost nonexistent; and African Muslim countries supported Moroccan independence. Additionally, the U.S. and the United Nations were in favor of the independence of the former colonies. Russia, along with its satellite countries, was also in favor of the independence of Morocco, just waiting for the moment for France’s withdrawal in order to easily move in with its communist agenda amidst the probable crisis situation the new country would face.

Meanwhile, towards the end of 1948, the Viet Minh army had been ejected to the north near the border with China. By then, French expeditionary forces were reduced to 108,000 men because of budgetary reasons and the French government decided to negotiate Vietnam’s independence with Bao Dai, in exchange for his allegiance to the French Union. However, Mao Tse-tung’s triumph drastically changed the situation and quickly strengthened the Viet Minh, initiating an offensive in February, 1950, that forced the French to withdraw in October of that same year.

The lack of French resources, the delay in the formation of the Vietnamese army, and the low feasibility of American support (bomber aircraft, air reconnaissance and weapons for the Vietnamese army), compounded by the need to protect Hanoi with an area of no surrender, led to the designation of a Commander to assume the risks that the situation imposed. The position of High Commissioner and Commander of Indochina was given to Marshal Jean de Lattre, who was tasked to cover the Northern Delta, inflict severe defeats on the Viet Minh, and urgently create a Vietnamese political / military organization, mainly by changing the general staff of the forces deployed in Indochina.

His plan was only partially fulfilled, as he died a year after taking office. His successor, General Salan, received on the one hand an equipped Vietnamese army – mainly because the Marshal himself visited Washington to ask for help - and, on the other hand, an enemy that had the capability to withstand a great deal of human loss by recruiting troops and obtaining rice from the Delta.

In 1953, Viet Minh forces had freedom of movement and advanced south/southwest towards Laos. French forces, with approximately 25 divisions, gathered like hedgehogs around airfields and had lost all mobility. Therefore, General Salan was relieved by General Henri Navarre to reverse this situation, that could become desperate if the rainy season ended and the Viet Minh resumed the offensive.

THE THEATER OF OPERATIONS AND ITS ENVIRONMENT – NAVARRE’S CAMPAIGN

General Navarre, who had no experience or knowledge of the Orient, was appointed to the command of Indochina forces on May 8, while he was serving as NATO Chief of Staff in Central Europe.

The mission entrusted to him was to obtain a favorable outcome of the conflict, since the French government understood that it was a lost cause, but he did not receive any guidance on how to achieve it. The first news that he received was that, beginning with his appointment, civil and military power were to be divided, and thus, he would not have total control over the Theater of Operations.

THE SITUATION UPON GENERAL NAVARRE’S ARRIVAL

POLITICAL

On May 18th, General Navarre left for Indochina. Upon his arrival, he found his staff and commandos totally disorganized, as senior officers were returning to France without any replacement. Therefore, he was forced to appoint new chiefs and to reorganize his General Staff both in terms of their methods of work and their composition, going from a predominantly ground staff to a joint combined one.

After inspecting the land and contacting all those involved in the region, he left on July 2 to present his plan of action to France, as he had been ordered. In his plan he requested the unification of the civilian and military authority in a single person or, at least, relegate the military authority only to a diplomatic function to fully conduct the war actions that the situation required. This proposal was dismissed by the new government that was in charge, appointing Ambassador Dejean as the General Commissioner. The government’s decision would certainly affect the conduct of war, but General Navarre knew the capacity and the sympathy that the Ambassador felt for the military, and believed that there would be no difficulty in working with him. The both returned to Saigon on October 1.

at this point. French politics did not favor actions of any kind: part of the political sector wanted an honorable exit by prolonging the war a little longer; the rest wanted an immediate exit at all costs, since they considered it a plan purely of the military establishment, after nineteen governments and seven commanders throughout seven years of war without a political objective. The political guidelines to recover the colonies passed to the creation of the independence of the Associated States within the framework of the French Union, this was only a cover to facilitate the departure of France from Indochina and the independence of the Indochinese states, although some intended a real union with France, thus taking sides with one side or the other. In this sense, the intervention of the USA in support would only result in any possible end the independence of Indochina.

The French military sector, which knew a little more about the situation in Indochina, wanted to end the war at all costs to rebuild its armed forces. Meanwhile, the Viet Minh had become a true state and created around it a national mystic that, in addition to indoctrination, served to legitimize a powerful authority over more than half of the population, while the rest of Indochina was completely divided. Under these conditions, the Viet Minh devoted all the forces of the nation to war, under the leadership of a single political leader and a military leader.

MILITARY AND GEOGRAPHIC

The French armed forces were not prepared for a war that was very different from Korea or the last Great War. This was a war without a front, supported by masses that carried out operations with regular forces. The French forces in Indochina concentrated on the Red River and the Mekong, where they protected the ports and bases; leaving the forested and mountainous areas in the hands of second order forces (Laotians, Thai, Moi and Cambodians), who were better adapted to that geography.

This situation changed when the forces of General Giap changed their center of gravity over the zone controlled by second order forces, transforming the theater of operations and following a strategic plan that was aligned with the organization of their armed forces, flexible, powerful and adapted to the country. His campaign forces consisted of seven infantry divisions with modern portable weaponry, with many independent regiments that raised the troops to nine divisions. In addition to a heavy division with artillery units, he had a unit of engineers and anti-aircraft defense. All this included a solid ideological faith and a bitter hatred of the enemy living with the people and supported by them.

On the other hand, French forces were not established without any strategy, and without continuity under various politico-military commands. It had tanks, artillery and aviation, but all this material, despite giving greater fire power, was designed for another type of war, since it was very difficult to mobilize it outside the route or through the narrow bridges of the region.

Despite this, the French controlled the Tonkin Delta, the coastal area as far as Mokay, and the fortified camps of Nasam and Laichau. The higher ground, Laos, was seriously compromised by the enemy occupation of Dien Bien Phu. The rest was controlled by rebel bands that were under the control of the Viet Minh. Which imposed a prompt reaction to prevent the imminent arrival of the enemy, who was already fully infiltrated and forced to place fixed positions in countless places (around five divisions) to ensure the routes, supply and protection of the premises.

Thus, French forces placed fixed positions in countless places (about five divisions) to ensure routes, supply and protection of the locals. This situation was exacerbated by China’s logistical support of the Viet Minh, whereas the logistical support of the French forces were thousands of kilometers away. Compounding the situation was the Viet Minh's ability to maintain secrecy and the lack of control on the French side due to the press, the large number of informants that the Viet Minh had, and the lack of government control the lack of awareness of the forces deployed in Indochina in the use of information. However, the French had greater firepower through their tanks, artillery and aviation, and strategic mobility via land transport (train and rail), maritime, and air, and a recently emerging army formed with its allied colonies.

"DIEN BIEN PHU": FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE DECISION-MAKING AT THE OPERATIONAL LEVEL - II

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2019 Quixote Globe

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2019 Quixote Globe